So, Karl Rove blames the President's low approval ratings on the war in Iraq. Okay, Karl... what's your point? If we aren't thrilled about the war, who should we disapprove of?

Maybe Karl thought we should disapprove of the soldiers. It's their fault; they're not fighting hard enough. They should take a page from the suicide bombers play book and make sure that if they're going to die that they take out a dozen insurgents with them. Or Iraqi civilians. Whatever. Just keep that body count climbing... for freedom!

It seems to me that in a goverment where the President also holds the title of commander in chief, and in which he asked Congress to give up their authority to commit military forces to him, it's only fair for the President to be the recipient of at least some of the disapproval that comes up when the poorly-planned, ill-advised, under-funded, unpopular, unilateral war is not going well.

At any rate, it seems that Rove feels it's too bad that people are focusing on this whole "war" thing, because Bush is really a swell guy. Or rather, he's "likeable."

That's right, Rove actually seemed to be giving more weight to Bush's "likability" rating than his approval rating. Rove is less concerned about whether people approve of the job the President is doing than he is with whether or not they "like" him.

I'm a little concerned when one of the President's top advisors (or whatever he is now) is very concerned that people find the Presidnet to be "likeable." I mean, likeability is an important trait for the main character of a sitcom or family drama. Especially if you give the main character Down's syndrome and make them incredibly naive, and then week after week have them duped into commiting crimes or mean pranks by people that they think are their friends ("But why would he lie? I don't understand..." "But he said it would help people, I don't understand..." "But he said he was my friend, I don't understand..."). Who's more likeable than Corky? Maybe Scooby-Doo. Or Mr. Bean. I like him a lot.

Problem is, I would be digging myself a bomb shelter in the backyard if any of these characters were actually President ("But he told me the button was for ice cream, not missiles! Why would he lie? I don't understand...") . It would be nice if I liked someone who was qualified to be President, but if it comes down to it, I'll vote for someone I don't particularly care to socialize with if I approve of the job they'll do or have done as President.

Maybe that's the Democrats' problem. I mean, how likeable were Gore or Kerry? This bodes poorly for the future: Hilary? Not really likeable. Scary, yes. Likeable? Uh... is Corky a Democrat?

- "You like me! You really like me!"

Monday, May 15, 2006

Friday, May 05, 2006

IVBCF Alum...

Hey, everyone,

On the off chance that you are a graduate of UCLA's InterVarsity Christian Fellowship Chapter, you are invited to the BCF Alumni Conference! For details, follow this link to another link on my brother's blog which will hopefully send you to the organizers and not an endless series of links.

- No quote, sorry.

On the off chance that you are a graduate of UCLA's InterVarsity Christian Fellowship Chapter, you are invited to the BCF Alumni Conference! For details, follow this link to another link on my brother's blog which will hopefully send you to the organizers and not an endless series of links.

- No quote, sorry.

Friday, April 07, 2006

Whoops! We CAN do better!

In November, I wrote a post about how the state's goal for school's API scores was 800, and how it was impossible for more than 40% of the schools to meet that goal. You know what? I was wrong... sort of. There is a way for 60% of school's to reach that target, but I still maintain that it's gonna be nigh impossible to get there.

Why? Well, imagine that there are 100 students in the country, and we rank them according to their test scores into quintiles (what's a quintile, you ask? Check this post out for an explanation). That would mean that 20 kids got a score of 200, 20 got a score of 400, 20 got a score of 600, 20 got a score of 800, and 20 got a score of 1000. You can see that only 40% of the students got 800 or above. The school's API, however, depends on the average of all of the students in the school. So it's possible to arrange the students so that the average is at or above 800 for more than 40% of the students.

How? Well, it's those kids that scored 1000. We can use their extra points to balance out some other kids who scored under 800. The simplest example would be to match up one student with a score of 1000 with one student with a score of 600. If those two students made up the entire school, that school would have an average API of 800. See? Easy, huh?

Unfortunately, it's only 20 percent of the students that have these extra points, so if we make 40 % of our schools populated with exactly half of their students in the 600 range and half in the 1000 range, we can bring up those schools to 800 as an average score. Keep all of the students who scored 800 together and their schools keep their 800 score, giving us another 20% of our schools meeting the target. Those kids who scored 200 or 400? Well, the problem is that we'd have to waste 2 or 3 1000 scoring kids on each one of those students to bring the average up to 800, which would mean less schools overall would have the average that we want. Sorry, bottom-percentilers. You lose, but America wins... right?

Not really. Notice that the only thing I'm doing is rearranging which schools these kids are going to. No increase in learning or improvement in instruction has to happen for more schools to come up to the statewide goal, we just need to mix the students up a little bit.

Actually, that's not a bad idea. I am not alone among educators who think that a heterogeneous population in a school and in individual classrooms makes for a better learning environment and improves learning for all students, even those at the top (of course, this won't necessarily improve test scores, since they don't measure learning, just ranking). So why do I say it's still impossible? Well, you'd probably be able to convice parents and students at a school averaging 600 that it's a good idea for some students from their school to be transferred to the school across town that averages 1000. The problem comes when you try to get parents and students (mostly parents) of the students at school 1000 to move over to school 600.

Well, I have a proposal that could actually make the standardized testing system marginally worthwhile. Not worthwhile enough to keep doing it the way we do, but less of a complete waste of time, energy, resources, and money. What if a federal mandate demands that all schools must be made up of a student population that has an average API of exactly 600? Testing would be given in 3rd grade, 6th grade, 9th grade, and 12th grade. Transfers would only be permissible in the 4th grade, 7th grade and 10th grade, and those transfers would have to rebalance the API averages in those schools back to 600. (It's cruel, ineffective, and nonsensical to administer standardized tests to kids before 3rd grade. They can't read well enough or sit still and focus long enough to make it worth the effort.) That way, every "Elementary B" school ("Elementary A" being Kindergarten through 3rd grade) would start off with the same average level of test-takers (notice I don't say that they're at the same level as far as actual knowledge or skill... just test-taking), and then the test that they take 3 years later would actually show whether their test-taking improved as a result of 3 years at that school or not (again, this wouldn't necessarily tell us anything about their learning during those 3 years, just their test-taking ability). Likewise for 7th -9th grade "Middle Schools" and 10th through 12th grade "High Schools." Any schools that scored above 600 would have improved their students test taking ability relative to the average improvements across the nation. Lower than 600? Well, that would be bad, wouldn't it?

It still wouldn't tell us much about whether the kids are learning anything, but at least it would be a fair comparison of the schools' test-prep abilities. It's a far cry from assessing actual knowledge, but isn't it better than testing for socio-economic status and race, which is what the tests as they're currently set-up do test for?

- "That's impossible, no one can give more than one hundred percent, by definition that is the most anyone can give."

Why? Well, imagine that there are 100 students in the country, and we rank them according to their test scores into quintiles (what's a quintile, you ask? Check this post out for an explanation). That would mean that 20 kids got a score of 200, 20 got a score of 400, 20 got a score of 600, 20 got a score of 800, and 20 got a score of 1000. You can see that only 40% of the students got 800 or above. The school's API, however, depends on the average of all of the students in the school. So it's possible to arrange the students so that the average is at or above 800 for more than 40% of the students.

How? Well, it's those kids that scored 1000. We can use their extra points to balance out some other kids who scored under 800. The simplest example would be to match up one student with a score of 1000 with one student with a score of 600. If those two students made up the entire school, that school would have an average API of 800. See? Easy, huh?

Unfortunately, it's only 20 percent of the students that have these extra points, so if we make 40 % of our schools populated with exactly half of their students in the 600 range and half in the 1000 range, we can bring up those schools to 800 as an average score. Keep all of the students who scored 800 together and their schools keep their 800 score, giving us another 20% of our schools meeting the target. Those kids who scored 200 or 400? Well, the problem is that we'd have to waste 2 or 3 1000 scoring kids on each one of those students to bring the average up to 800, which would mean less schools overall would have the average that we want. Sorry, bottom-percentilers. You lose, but America wins... right?

Not really. Notice that the only thing I'm doing is rearranging which schools these kids are going to. No increase in learning or improvement in instruction has to happen for more schools to come up to the statewide goal, we just need to mix the students up a little bit.

Actually, that's not a bad idea. I am not alone among educators who think that a heterogeneous population in a school and in individual classrooms makes for a better learning environment and improves learning for all students, even those at the top (of course, this won't necessarily improve test scores, since they don't measure learning, just ranking). So why do I say it's still impossible? Well, you'd probably be able to convice parents and students at a school averaging 600 that it's a good idea for some students from their school to be transferred to the school across town that averages 1000. The problem comes when you try to get parents and students (mostly parents) of the students at school 1000 to move over to school 600.

Well, I have a proposal that could actually make the standardized testing system marginally worthwhile. Not worthwhile enough to keep doing it the way we do, but less of a complete waste of time, energy, resources, and money. What if a federal mandate demands that all schools must be made up of a student population that has an average API of exactly 600? Testing would be given in 3rd grade, 6th grade, 9th grade, and 12th grade. Transfers would only be permissible in the 4th grade, 7th grade and 10th grade, and those transfers would have to rebalance the API averages in those schools back to 600. (It's cruel, ineffective, and nonsensical to administer standardized tests to kids before 3rd grade. They can't read well enough or sit still and focus long enough to make it worth the effort.) That way, every "Elementary B" school ("Elementary A" being Kindergarten through 3rd grade) would start off with the same average level of test-takers (notice I don't say that they're at the same level as far as actual knowledge or skill... just test-taking), and then the test that they take 3 years later would actually show whether their test-taking improved as a result of 3 years at that school or not (again, this wouldn't necessarily tell us anything about their learning during those 3 years, just their test-taking ability). Likewise for 7th -9th grade "Middle Schools" and 10th through 12th grade "High Schools." Any schools that scored above 600 would have improved their students test taking ability relative to the average improvements across the nation. Lower than 600? Well, that would be bad, wouldn't it?

It still wouldn't tell us much about whether the kids are learning anything, but at least it would be a fair comparison of the schools' test-prep abilities. It's a far cry from assessing actual knowledge, but isn't it better than testing for socio-economic status and race, which is what the tests as they're currently set-up do test for?

- "That's impossible, no one can give more than one hundred percent, by definition that is the most anyone can give."

Labels:

education,

politics,

standardized tests,

statistics

Thursday, April 06, 2006

Myths About Immigration #1 - We're paying for their education

Facts:

According to the US Census bureau, there were 53.6 Million Children between the ages of 5 and 18 in the US in 2004 (most recent numbers available). There were 2.3 Million non-citizens in the US under the age of 18. That means that 4.3% of school-age children in the US were not citizens. Most estimates put the proportion of these non-citizens that are in the country illegally (or "undocumented" if you will) at roughly half. That means that about 2% of school-age children in the US are undocumented immigrants.

According to the National Educators Association, the nationwide average cost of education per pupil (as of 2006) is $7,552. That means that educating every child in America between the ages of 5 and 18 would cost about 400 Billion dollars per year in total (including federal, state, and local funds). The cost of educating the undocumented immigrants who are between the ages of 5 and 18? About 8 Billion dollars per year.

8 Billion dollars is nothing to sneeze at, to be sure. So how can we get that money back? Well, we could deport all of these kids. I'd assume that we'd go ahead and deport their families, too. A conservative anti-immigration group reported that it would cost about $200 Billion over 5 years to deport all of the illegal immigrants currently in the US (assuming that no more come in, that is). We can imagine that this estimate is on the low side, given the political ideology of the source. So, if we do that, we'll break even in about... 25 years. But wait, there's more! In order to keep any more illegals from crossing the border during those 25 years, we would need to beef up border security to the tune of 2-10 Billion dollars per year. Let's be conservative and say $5 Billion per year. That adds 125 Billion that we need to make up for, which adds another 16 years, making it 41 years before we break even on our deportation based on that $8 Billion a year we save by not having to educate undocumented kids. But wait, during those 41 years we're only nnetting $3 Billion a year, since we're using $5 Billion to keep the immigrants from coming back in each year. So it's actually more than 65 years before we start netting $3 Billion a year. $3 Billion out of an annual deficit of 500 Billion, meaning... our deficit is only 99.4% of what it would otherwise be. Whoo-hoo! We can't afford to keep these kids in our schools!

Of course I've made a lot of assumptions that are open to debate, which is fine. The biggest assumption is that schooling these kids is the only public cost of illegal immigration. I'm sure that lots of people can come up with lots of other ways we'll save money by giving them the boot which will more than make up for the $50 Billion per year cost of deporting them and keeping them out (okay, after 5 years it goes down to about $10 Billion per year, sorry for trying to mislead you with statistics). That's why this is Part 1 of a series. I'll examine the other supposed ways in which immigrants are a drain on our economy ("myths" as I've called them in my title) and try to offer convincing evidence that deporting undocumented immigrants will actually put the biggest hurt on our economy since... well, since W. got elected, I guess.

- "Oh, it's a PROFIT deal!"

According to the US Census bureau, there were 53.6 Million Children between the ages of 5 and 18 in the US in 2004 (most recent numbers available). There were 2.3 Million non-citizens in the US under the age of 18. That means that 4.3% of school-age children in the US were not citizens. Most estimates put the proportion of these non-citizens that are in the country illegally (or "undocumented" if you will) at roughly half. That means that about 2% of school-age children in the US are undocumented immigrants.

According to the National Educators Association, the nationwide average cost of education per pupil (as of 2006) is $7,552. That means that educating every child in America between the ages of 5 and 18 would cost about 400 Billion dollars per year in total (including federal, state, and local funds). The cost of educating the undocumented immigrants who are between the ages of 5 and 18? About 8 Billion dollars per year.

8 Billion dollars is nothing to sneeze at, to be sure. So how can we get that money back? Well, we could deport all of these kids. I'd assume that we'd go ahead and deport their families, too. A conservative anti-immigration group reported that it would cost about $200 Billion over 5 years to deport all of the illegal immigrants currently in the US (assuming that no more come in, that is). We can imagine that this estimate is on the low side, given the political ideology of the source. So, if we do that, we'll break even in about... 25 years. But wait, there's more! In order to keep any more illegals from crossing the border during those 25 years, we would need to beef up border security to the tune of 2-10 Billion dollars per year. Let's be conservative and say $5 Billion per year. That adds 125 Billion that we need to make up for, which adds another 16 years, making it 41 years before we break even on our deportation based on that $8 Billion a year we save by not having to educate undocumented kids. But wait, during those 41 years we're only nnetting $3 Billion a year, since we're using $5 Billion to keep the immigrants from coming back in each year. So it's actually more than 65 years before we start netting $3 Billion a year. $3 Billion out of an annual deficit of 500 Billion, meaning... our deficit is only 99.4% of what it would otherwise be. Whoo-hoo! We can't afford to keep these kids in our schools!

Of course I've made a lot of assumptions that are open to debate, which is fine. The biggest assumption is that schooling these kids is the only public cost of illegal immigration. I'm sure that lots of people can come up with lots of other ways we'll save money by giving them the boot which will more than make up for the $50 Billion per year cost of deporting them and keeping them out (okay, after 5 years it goes down to about $10 Billion per year, sorry for trying to mislead you with statistics). That's why this is Part 1 of a series. I'll examine the other supposed ways in which immigrants are a drain on our economy ("myths" as I've called them in my title) and try to offer convincing evidence that deporting undocumented immigrants will actually put the biggest hurt on our economy since... well, since W. got elected, I guess.

- "Oh, it's a PROFIT deal!"

Saturday, March 11, 2006

Just for fun...

I'm taking a technology class to clear my teaching credential, and we played with Photoshop for a couple hours this morning. Here's my final product:

What do you think? Should I go for it?

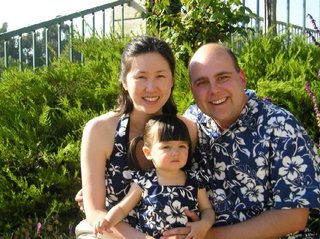

Edit: I guess for any strangers reading this, it's more dramatic if you know what I look like without digital enhancement (and you get to see my lovely wife and daughter, too!):

- "I don't wear a hairpiece!"

Friday, March 10, 2006

Screw the future, we're zillionaires!

I'm getting the feeling that the current adminstration is unaware of the nature of space-time. They seem to be living in an eternal present, disconnected to any past from which lessons can be learned or from any future in which current actions might have some consequences.

Evidence for a disdain of the past has probably been most popularly celebrated in the many comparisons of the war in Iraq to the war in Vietnam. A less obvious but just as poignant observation could be made if we compare the culture of secrecy and acting with impunity to the culture of the Nixon White House that led to Watergate.

What I think is more interesting, however, is the apparent lack of acknowledgement of the future. Time and again, policies have been set forth, stances have been taken, and actions have been approved that seem to indicate that the current administration is unaware of the fact that the world will continue after W's term in office comes to an end, or even that it will come to an end. They seem particularly unaware of the possibility of anyone with whom they are not idealogically aligned ever occupying any position of power in this country ever again.

The latest evidence of this temporal blind-spot is Bush's desire to have line-item veto power. Doesn't he realize that the Congress can't legislate that power for him with the qualifier "this power only applies to conservative republican presidents with ties to the petroleum industry in wartime against a noun such as 'terror,' 'weather,' or 'sadness'"? If he gets line-item veto power, so will all of the presidents who come after him, some of whom he's sure to disagree with on just about every point of import. But he doesn't seem to care...

Coupled with the move to authorize the NSA to spy domestically without warrants, the executive branch has made moves to dilute the power of the legislative branch (line-item veto) and the judicial branch (no warrants). In fact, it seems like this administration has the goal of investing as much power in the person of the president as possible and tilting the system of checks and balances toward the president so far as to threaten upsetting the whole system.

There is, I suppose, a sort of logic to what they are doing: a logic that one would expect to be employed by a 6 year old when they devise a bold plan to raid the cookie jar and assume that they will never get caught because they're so brilliant. They have control of the White House and both houses of congress at the same time. There may not be another opportunity to get the congress to willingly grant a great deal of its own power to the executive branch. The implications of such transfer seem to be moot. Isn't there at least one intern hanging around one of these meetings waiting to see if anyone wants coffee who's saying, "Hey, what if the next president is a democrat, and we still control congress but we've given the president so much power that he can still do whatever the heck he wants?" Shouldn't they be scared to death of setting up just such a scenario?

Or maybe they just don't care. Here's my theory: the actual goal of everything they do is to make sure that they and their wealthy friends get as much cash as is humanly possible in the next two and a half years. At that point, who cares what happens? They're filthy rich! If you have bazillions of dollars, you can pretty much ride above the petty concerns of regular humanity like famine, pestilence and war.

What do you think? It seems to explain a lot of the otherwise inscrutable behavior we see coming out of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. The two pronged attack of making sure that the wealthy pay as little as possible for taxes, and then giving as much of the money actually collected from the middle classes to defense contractors and Halliburton sets these guys up pretty nicely for the next 15 or 20 years (or less, if you're Cheney. I mean, how many heart-attacks does this guy have left? Ditto for anyone who goes hunting with him). By embroiling us in a war against a military tactic as oppossed to any actual set of persons (terrorism isn't genetic: you don't have to be born to a terrorist to be able to practice it. Therefore, getting rid of all of the terrorists isn't actually getting rid of terrorism. Milosevic had a much more achievable goal...), they're also setting up a continuous stream of income for all of those guys well into their retirement. It's a perfect plan. The events of 9/11 worked better than the hijackers could have hoped. It put us in the mindset of fear that led us to say "do whatever you want, just protect us from this sort of thing," and then accept unprecedented tax cuts and sketchy justifications for war as being somehow connected to what we were afraid of.

Oh, well, you know what they say: In a democracy, you get the leadership you deserve. I'll bet Iraqis can't wait!

- "No nation is permitted to live in ignorance with impunity." (I'm cheating, this is a historical quote, not from a movie)

Evidence for a disdain of the past has probably been most popularly celebrated in the many comparisons of the war in Iraq to the war in Vietnam. A less obvious but just as poignant observation could be made if we compare the culture of secrecy and acting with impunity to the culture of the Nixon White House that led to Watergate.

What I think is more interesting, however, is the apparent lack of acknowledgement of the future. Time and again, policies have been set forth, stances have been taken, and actions have been approved that seem to indicate that the current administration is unaware of the fact that the world will continue after W's term in office comes to an end, or even that it will come to an end. They seem particularly unaware of the possibility of anyone with whom they are not idealogically aligned ever occupying any position of power in this country ever again.

The latest evidence of this temporal blind-spot is Bush's desire to have line-item veto power. Doesn't he realize that the Congress can't legislate that power for him with the qualifier "this power only applies to conservative republican presidents with ties to the petroleum industry in wartime against a noun such as 'terror,' 'weather,' or 'sadness'"? If he gets line-item veto power, so will all of the presidents who come after him, some of whom he's sure to disagree with on just about every point of import. But he doesn't seem to care...

Coupled with the move to authorize the NSA to spy domestically without warrants, the executive branch has made moves to dilute the power of the legislative branch (line-item veto) and the judicial branch (no warrants). In fact, it seems like this administration has the goal of investing as much power in the person of the president as possible and tilting the system of checks and balances toward the president so far as to threaten upsetting the whole system.

There is, I suppose, a sort of logic to what they are doing: a logic that one would expect to be employed by a 6 year old when they devise a bold plan to raid the cookie jar and assume that they will never get caught because they're so brilliant. They have control of the White House and both houses of congress at the same time. There may not be another opportunity to get the congress to willingly grant a great deal of its own power to the executive branch. The implications of such transfer seem to be moot. Isn't there at least one intern hanging around one of these meetings waiting to see if anyone wants coffee who's saying, "Hey, what if the next president is a democrat, and we still control congress but we've given the president so much power that he can still do whatever the heck he wants?" Shouldn't they be scared to death of setting up just such a scenario?

Or maybe they just don't care. Here's my theory: the actual goal of everything they do is to make sure that they and their wealthy friends get as much cash as is humanly possible in the next two and a half years. At that point, who cares what happens? They're filthy rich! If you have bazillions of dollars, you can pretty much ride above the petty concerns of regular humanity like famine, pestilence and war.

What do you think? It seems to explain a lot of the otherwise inscrutable behavior we see coming out of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. The two pronged attack of making sure that the wealthy pay as little as possible for taxes, and then giving as much of the money actually collected from the middle classes to defense contractors and Halliburton sets these guys up pretty nicely for the next 15 or 20 years (or less, if you're Cheney. I mean, how many heart-attacks does this guy have left? Ditto for anyone who goes hunting with him). By embroiling us in a war against a military tactic as oppossed to any actual set of persons (terrorism isn't genetic: you don't have to be born to a terrorist to be able to practice it. Therefore, getting rid of all of the terrorists isn't actually getting rid of terrorism. Milosevic had a much more achievable goal...), they're also setting up a continuous stream of income for all of those guys well into their retirement. It's a perfect plan. The events of 9/11 worked better than the hijackers could have hoped. It put us in the mindset of fear that led us to say "do whatever you want, just protect us from this sort of thing," and then accept unprecedented tax cuts and sketchy justifications for war as being somehow connected to what we were afraid of.

Oh, well, you know what they say: In a democracy, you get the leadership you deserve. I'll bet Iraqis can't wait!

- "No nation is permitted to live in ignorance with impunity." (I'm cheating, this is a historical quote, not from a movie)

Tuesday, February 28, 2006

Instead of a strike...

I have some ideas for action that teachers can take instead of striking to address inequity issues. I've tried to come up with actions that are about denying service to our employers (district, state) while continuing to provide service to our students. Most of these have some sort of financial consequence attached to them, too, which might make them more effective actions:

- What if we refuse to administer Standardized tests? We still come to work, but we just teach on those days and don't do the tests. Far from being something that hurts our students, I think this would actually help them (since taking those tests is of no benefit to them at all), and at the same time throws a monkey wrench into the district and state bureaucracies.

- (This is my favorite) What if we refuse to comply with district requests that we kowtow to "high profile" parents and bend over backward to meet their demands at the expense of the vast majority of our poor students who are not politically connected or economically powerful? What if we instead partner with the Union and the district to encourage those parents to join class action lawsuits against the state and federal governments for not adequately funding education to allow us to provide mandated services to all students? I personally would feel very free to tell a parent that I cannot provide a service to their child that I would not also be able to provide at the same level to every child in my charge with similar needs within the parameters of my contract. Let's turn these parents with financial and political clout into our allies to fight for funding for all students!

Wouldn't that be great? Wouldn't it be worthwhile? Wouldn't it be better directed at those who are perpetuating the problem and victimizing our kids (especially the poor kids) instead of turning those same kids into "collateral damage" in a messy battle that they have no control over?

What do you think?

- "...but you can't make an omelette without breaking a few eggs!"

- What if we refuse to administer Standardized tests? We still come to work, but we just teach on those days and don't do the tests. Far from being something that hurts our students, I think this would actually help them (since taking those tests is of no benefit to them at all), and at the same time throws a monkey wrench into the district and state bureaucracies.

- (This is my favorite) What if we refuse to comply with district requests that we kowtow to "high profile" parents and bend over backward to meet their demands at the expense of the vast majority of our poor students who are not politically connected or economically powerful? What if we instead partner with the Union and the district to encourage those parents to join class action lawsuits against the state and federal governments for not adequately funding education to allow us to provide mandated services to all students? I personally would feel very free to tell a parent that I cannot provide a service to their child that I would not also be able to provide at the same level to every child in my charge with similar needs within the parameters of my contract. Let's turn these parents with financial and political clout into our allies to fight for funding for all students!

Wouldn't that be great? Wouldn't it be worthwhile? Wouldn't it be better directed at those who are perpetuating the problem and victimizing our kids (especially the poor kids) instead of turning those same kids into "collateral damage" in a messy battle that they have no control over?

What do you think?

- "...but you can't make an omelette without breaking a few eggs!"

Friday, February 24, 2006

What if it isn't just a movie...

Suppose you sent a person and then a robot back in time from the future 3 times in order to prevent some calamity, but every time you think you've prevented it, it finds some other way to happen?

Suppose the future you're trying to prevent is the development of computers so sophisticated that they become self-aware and turn on their human inventors?

Suppose you've decided after the first 3 attempts fail, to try a much subtler approach?

If the educational system can be decimated to such a degree that the chances of anyone actually educated under this system being able to develop anything nearly as sophisticated as the machines from the future becomes next to impossible, wouldn't it make sense to send back a killer robot to wreak just such havoc upon the educational system?

That's right, we're all extras in Terminator 4: Return to the Stone Age.

I hope that Arnold is able to get to me before a crazed Sarah Connor breaks into my classroom in combat fatigues and threatens to eviscerate me in front of my students: "It was you! You taught them math! You made it possible! I have to stop you!" If he cuts off his fake skin and shows me his robotic arm, I'll help him take down the system from the inside... not with explosives, but by filling up instruction time with meaningless tests, making it harder for anyone to become a teacher, and using up as much education funding as possible to create tax breaks for the wealthy (as long as they're not wealthy computer programmers).

If it ends with me propped up against a desk, clutching a heavy text-book above the "enter" key set to execute a program that increases community college funds, gasping "I don't know... how much longer... I can hold this..." as underprivileged students dive for cover, then that's just what I'll have to do. .. although I'd much rather be the guy who tearfully lowers Arnold into the steaming cauldron of the hot tub behind his mansion after he saves the world from education.

- "I'll be back."

Suppose the future you're trying to prevent is the development of computers so sophisticated that they become self-aware and turn on their human inventors?

Suppose you've decided after the first 3 attempts fail, to try a much subtler approach?

If the educational system can be decimated to such a degree that the chances of anyone actually educated under this system being able to develop anything nearly as sophisticated as the machines from the future becomes next to impossible, wouldn't it make sense to send back a killer robot to wreak just such havoc upon the educational system?

That's right, we're all extras in Terminator 4: Return to the Stone Age.

I hope that Arnold is able to get to me before a crazed Sarah Connor breaks into my classroom in combat fatigues and threatens to eviscerate me in front of my students: "It was you! You taught them math! You made it possible! I have to stop you!" If he cuts off his fake skin and shows me his robotic arm, I'll help him take down the system from the inside... not with explosives, but by filling up instruction time with meaningless tests, making it harder for anyone to become a teacher, and using up as much education funding as possible to create tax breaks for the wealthy (as long as they're not wealthy computer programmers).

If it ends with me propped up against a desk, clutching a heavy text-book above the "enter" key set to execute a program that increases community college funds, gasping "I don't know... how much longer... I can hold this..." as underprivileged students dive for cover, then that's just what I'll have to do. .. although I'd much rather be the guy who tearfully lowers Arnold into the steaming cauldron of the hot tub behind his mansion after he saves the world from education.

- "I'll be back."

Thursday, February 09, 2006

Why I Won't Strike: Second Draft

Okay, here's my second draft. I'd appreciate feedback! Feel free to send this to anyone else that you think might have thoughts on this topic. (The first draft is the post immediately preceding this one.)

Funding education is the primary way in which we as a people collectively invest in our children. While everyone is willing to invest in their own education and their own children's education, our fiscal policies betray how little other people’s children are valued; for a budget is surely a moral document, setting forth those things that we deem worth investing in and those we begrudgingly allow to pick up the crumbs which fall from the table. Children are politically and economically weak and vulnerable, and the machine that drives our policy is at best indifferent (but more often hostile) to the needs of a demographic that doesn't vote, pay taxes, or contribute to political campaigns.

That is why I am a teacher. In a world where children receive a clear message that they are not valuable to society at large, my hope is that my presence, my work, and my care for my students communicates to them that one person, at least, does value them and has chosen to link my life and my fortunes to theirs. The ethos of the teaching profession is a frank rejection of the prevailing culture’s assumption that our career paths are determined first and foremost on the basis of economic factors, since all of us have a degree of training and education that would qualify us for a substantially higher pay scale in the private sector. A teacher’s salary does not represent fair compensation for services rendered, for if it did, we would surely be paid far more. Instead, our salary allows us to spend our time in the classroom with our students rather than being forced to go out and find other employment to provide food, clothing and shelter for ourselves and our families. This stance makes us vulnerable, for the powers that be know that a people driven by compassion for those they serve will not readily forsake those served for their own economic self interest. Our willingness to forego a higher paying career for the sake of our vocation opens us up to be taken advantage of by those who are counting on our unwillingness to abandon our students.

So, how are we to respond when our vulnerabilities are exploited? One option is to call their bluff, and walk out on our position, forcing those who hold the purse strings to meet our demands or lose our services. This option is an attempt to turn an inherently weak and vulnerable position into one of strength; to use threats and power to force others to our will. If we take this path, we offer validation to those who operate under the presumption that might makes right by adopting their methods as our own.

I will not take this path. It is true that our children are not valued, and they are left weak and vulnerable to those mercenaries in power whose influence is available to the highest bidder. By virtue of my education and socio-economic status, I have access to the benefits that the system holds out to those as fortunate as I have been. My students do not have the options that I have. I choose, therefore, to throw in my lot with my students, to let their fortunes be mine, to give up the level of control over my own life that society offers to me and instead subject myself to the caprices of the powerful. I will raise my voice to decry the injustices that marginalize my students and their families, but I will not abandon my students when those same injustices throw my life into the same kind of uncertainty that is their daily reality. I am a teacher, and my professional life is lived for the sake of those I serve. Though they are despised by society, I honor them, and to the extent that I am able to join them in their suffering, I receive it as an honor that the world at large cannot recognize, but which is of greater value than any concessions that can be won by the threat or enactment of a strike.

- "If might is right, then love has no place in the world. It may be so, it may be so. But I don't have the strength to live in a world like that..."

Funding education is the primary way in which we as a people collectively invest in our children. While everyone is willing to invest in their own education and their own children's education, our fiscal policies betray how little other people’s children are valued; for a budget is surely a moral document, setting forth those things that we deem worth investing in and those we begrudgingly allow to pick up the crumbs which fall from the table. Children are politically and economically weak and vulnerable, and the machine that drives our policy is at best indifferent (but more often hostile) to the needs of a demographic that doesn't vote, pay taxes, or contribute to political campaigns.

That is why I am a teacher. In a world where children receive a clear message that they are not valuable to society at large, my hope is that my presence, my work, and my care for my students communicates to them that one person, at least, does value them and has chosen to link my life and my fortunes to theirs. The ethos of the teaching profession is a frank rejection of the prevailing culture’s assumption that our career paths are determined first and foremost on the basis of economic factors, since all of us have a degree of training and education that would qualify us for a substantially higher pay scale in the private sector. A teacher’s salary does not represent fair compensation for services rendered, for if it did, we would surely be paid far more. Instead, our salary allows us to spend our time in the classroom with our students rather than being forced to go out and find other employment to provide food, clothing and shelter for ourselves and our families. This stance makes us vulnerable, for the powers that be know that a people driven by compassion for those they serve will not readily forsake those served for their own economic self interest. Our willingness to forego a higher paying career for the sake of our vocation opens us up to be taken advantage of by those who are counting on our unwillingness to abandon our students.

So, how are we to respond when our vulnerabilities are exploited? One option is to call their bluff, and walk out on our position, forcing those who hold the purse strings to meet our demands or lose our services. This option is an attempt to turn an inherently weak and vulnerable position into one of strength; to use threats and power to force others to our will. If we take this path, we offer validation to those who operate under the presumption that might makes right by adopting their methods as our own.

I will not take this path. It is true that our children are not valued, and they are left weak and vulnerable to those mercenaries in power whose influence is available to the highest bidder. By virtue of my education and socio-economic status, I have access to the benefits that the system holds out to those as fortunate as I have been. My students do not have the options that I have. I choose, therefore, to throw in my lot with my students, to let their fortunes be mine, to give up the level of control over my own life that society offers to me and instead subject myself to the caprices of the powerful. I will raise my voice to decry the injustices that marginalize my students and their families, but I will not abandon my students when those same injustices throw my life into the same kind of uncertainty that is their daily reality. I am a teacher, and my professional life is lived for the sake of those I serve. Though they are despised by society, I honor them, and to the extent that I am able to join them in their suffering, I receive it as an honor that the world at large cannot recognize, but which is of greater value than any concessions that can be won by the threat or enactment of a strike.

- "If might is right, then love has no place in the world. It may be so, it may be so. But I don't have the strength to live in a world like that..."

Tuesday, February 07, 2006

Why I Won't Strike

I wrote a while back about my struggles over the question of whether to join in a strike if it comes to that in my school district. Here's where I've landed after a lot of reflection, discussion, and prayer. This is a first draft, so I'd appreciate your input, especially since I'm thinking of reading this at our union general assembly where we're supposed to vote on whether to grant strike authorization to our negotiating team. (First of all, I think it's much too long, so I'd appreciate you letting me know what points seem worth making and what seems to just be repetitious or tangential. Any other feedback would be great, too!)

Education is not valued by our society. Everyone values their own education, and their own children's education, to be sure, but when it comes to funding the education of other people's children, our budget betrays our values; for a budget is surely a moral document, setting forth those things that we deem worth investing in and those we begrudgingly allow to pick up the crumbs which fall from the table. This relegation of education to the basement of our fiscal priorities is evident when we look at the budgets and policies of government at national, state, and local levels.

Funding education is the primary way in which we as a people collectively invest in our children. The woeful state of education funding is direct evidence of how little other people's children are valued at a political and economic level. Children are politically and economically weak and vulnerable, and the machine that drives our policy is at best indifferent (but more often hostile) to the needs of a demographic that doesn't vote, pay taxes, or contribute to political campaigns.

That is why I am a teacher. In a world where children receive a clear message that they are not valuable to society at large, I hope that my presence, my work, and my care for my students communicates to them that one person, at least, does value them and has chosen to link my life and my fortunes to theirs. We all know that the ethos of the teaching profession is not driven by economics: all of us have a degree of training and education that would qualify us for a substantially higher pay scale in the private sector. For us, our salary does not represent fair compensation for the services we render, for if it did, we would surely be paid far more. Instead, our salary allows us to spend our time in the classroom with our students rather than being forced to go out and find other employment to provide food, clothing and shelter for ourselves and our families. This stance makes us vulnerable, for the powers that be know that a people driven by compassion for those they serve will not readily forsake those served for their own economic self interest. Our willingness to forego a higher paying career for the sake of our vocation opens us up to be taken advantage of by those who are counting on our unwillingness to abandon our students.

So, what are we to do? One option is to call their bluff, and walk out on our position, forcing those who have the power to determine our financial fate to deal with us or lose our services. This option is an attempt to turn an inherently weak and vulnerable position into one of strength; to use threats and power to force others to our will. This brings us into the extended family of those who embrace force and power as the means to enforce our will on others. We make ourselves distant cousins to both those who set US policy in Iraq and Afghanistan on one side and with the leaders of the street gangs with whom we too often find ourselves in direct competition for the loyalties and future of our students on the other. We at once validate their methodology and deny our own better selves by declaring that yes, strength is the ultimate arbiter of truth and the arena for deciding our values.

I will not take this path. It is true that our children are not valued, and they are left weak and vulnerable to those mercenaries in power whose influence is available to the highest bidder. By virtue of my education and socio-economic status, I have access to the benefits that the system holds out to those as fortunate as I have been. My students do not have the options that I have. I choose, therefore, to throw in my lot with my students, to let their fortunes be mine, to give up the level of control over my own life that society offers to me and instead subject myself to the caprices of the powerful. I will raise my voice to decry the injustices that marginalize my students and their families, but I will not abandon my students when those same injustices throw my life into the same kind of uncertainty that is the daily reality my students live with. I am a teacher, and my professional life is lived for the sake of those I serve. Though they are despised by society, I honor them, and to the extent that I am able to join them in their suffering, I receive it as an honor that the world at large cannot recognize, but which is of greater value than any concessions that can be won by the threat of a strike.

- "If might is right, then love has no place in the world. It may be so, it may be so. But I don't have the strength to live in a world like that..."

Education is not valued by our society. Everyone values their own education, and their own children's education, to be sure, but when it comes to funding the education of other people's children, our budget betrays our values; for a budget is surely a moral document, setting forth those things that we deem worth investing in and those we begrudgingly allow to pick up the crumbs which fall from the table. This relegation of education to the basement of our fiscal priorities is evident when we look at the budgets and policies of government at national, state, and local levels.

Funding education is the primary way in which we as a people collectively invest in our children. The woeful state of education funding is direct evidence of how little other people's children are valued at a political and economic level. Children are politically and economically weak and vulnerable, and the machine that drives our policy is at best indifferent (but more often hostile) to the needs of a demographic that doesn't vote, pay taxes, or contribute to political campaigns.

That is why I am a teacher. In a world where children receive a clear message that they are not valuable to society at large, I hope that my presence, my work, and my care for my students communicates to them that one person, at least, does value them and has chosen to link my life and my fortunes to theirs. We all know that the ethos of the teaching profession is not driven by economics: all of us have a degree of training and education that would qualify us for a substantially higher pay scale in the private sector. For us, our salary does not represent fair compensation for the services we render, for if it did, we would surely be paid far more. Instead, our salary allows us to spend our time in the classroom with our students rather than being forced to go out and find other employment to provide food, clothing and shelter for ourselves and our families. This stance makes us vulnerable, for the powers that be know that a people driven by compassion for those they serve will not readily forsake those served for their own economic self interest. Our willingness to forego a higher paying career for the sake of our vocation opens us up to be taken advantage of by those who are counting on our unwillingness to abandon our students.

So, what are we to do? One option is to call their bluff, and walk out on our position, forcing those who have the power to determine our financial fate to deal with us or lose our services. This option is an attempt to turn an inherently weak and vulnerable position into one of strength; to use threats and power to force others to our will. This brings us into the extended family of those who embrace force and power as the means to enforce our will on others. We make ourselves distant cousins to both those who set US policy in Iraq and Afghanistan on one side and with the leaders of the street gangs with whom we too often find ourselves in direct competition for the loyalties and future of our students on the other. We at once validate their methodology and deny our own better selves by declaring that yes, strength is the ultimate arbiter of truth and the arena for deciding our values.

I will not take this path. It is true that our children are not valued, and they are left weak and vulnerable to those mercenaries in power whose influence is available to the highest bidder. By virtue of my education and socio-economic status, I have access to the benefits that the system holds out to those as fortunate as I have been. My students do not have the options that I have. I choose, therefore, to throw in my lot with my students, to let their fortunes be mine, to give up the level of control over my own life that society offers to me and instead subject myself to the caprices of the powerful. I will raise my voice to decry the injustices that marginalize my students and their families, but I will not abandon my students when those same injustices throw my life into the same kind of uncertainty that is the daily reality my students live with. I am a teacher, and my professional life is lived for the sake of those I serve. Though they are despised by society, I honor them, and to the extent that I am able to join them in their suffering, I receive it as an honor that the world at large cannot recognize, but which is of greater value than any concessions that can be won by the threat of a strike.

- "If might is right, then love has no place in the world. It may be so, it may be so. But I don't have the strength to live in a world like that..."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)